Lecture 4 - Analog frontend and filters

If you find an error in what I’ve made, then fork, fix lectures/l04_afe.md, commit, push and create a pull request. That way, we use the global brain power most efficiently, and avoid multiple humans spending time on discovering the same error.

- Introduction

- Filters

- First order filter

- Second order filter

- Gm-C

- Active-RC

- The OTA is not ideal

- Example circuit

Introduction

The world is analog, and these days, we do most signal processing in the digital domain. With digital signal processing we can reuse the work of others, buy finished IPs, and probably do processing at lower cost than for analog.

Analog signals, however, might not be suitable for conversion to digital.

A sensor might have a high, or low impedance, and have the signal in the voltage, current, charge or other domain.

To translate the sensor signal into something that can be converted to digital we use analog front-ends (AFE). How the AFE looks will depend on application, but it’s common to have amplification, frequency selectivity or domain transfer, for example current to voltage.

An ADC will have a sample rate, and will alias (or fold) any signal above half the sample rate, as such, we also must include a anti-alias filter in AFE that reduces any signal outside the bandwidth of the ADC as close to zero as we need.

One example of an analog frontend is the recieve chain of a typical radio, shown below. The signal that arrives at the antenna, or the “sensor”, can be weak, maybe -90 dBm, which is a power of $10^{-90/10} \times 1\text{ mW } = 1\text{ pW }$ or 50 $\mu$V RMS in 50 Ohm.

At the same time, at another frequency, there could be a signal of 0 dBm, or 0 mW, or 50 mV in 50 Ohm.

As such, there is a 1000 times difference between the wanted signal and the unwanted signal. Assume for the moment we actually used an ADC at the antenna, how many bits would we need?

Bluetooth uses Gaussian Frequency Shift Keying, which is a constant envelope binary modulation, and it’s ususally sufficient with low number of bits, assume 8-bits for the signal is more than enough.

But with the unwanted signal being 1000 times bigger, we would need an additional 10-bits, in total 18-bits. If we were to sample at 5 GHz, to ensure the bandwidth is sufficient for a 2.480 GHz maximum frequency we can actually compute the power consumption.

Given the Walden figure of merit of $FOM = \frac{P}{2^{ENOB}fs}$. The best FOM in literature is about 1 fJ/step, so $P = 1\text{ fJ/step} \times 2^{18} \times 5\text{GHz} = 1.31\text{ W}$, which is not an impossible number, but it’s certainly not what Bluetooth ICs do, because they consume around 20 mW in recieve mode.

The radio below has multiple blocks in the AFE. First is low-noise amplifier (LNA) amplifying the signal by maybe 10 times. The LNA reduces the noise impact of the following blocks. The next is the complex mixer stage, which shifts the input signal from radio frequency down to a low frequency, but higher than the bandwidth of the wanted signal. Then there is a complex anti-alias filter, also called a poly-phase filter, which rejects parts of the unwanted signals. Lastly there is a complex ADC to convert to digital.

In digital we can further filter to select exactly the wanted signal. Digital filters can have high stop band attenuation at a low power and cost. There could also be digital mixers to further reduce the frequency.

The AFE makes the system more efficient. In the 5 GHz ADC output, from the example above, there’s lot’s of information that we don’t use.

An AFE can reduce the system power consumption by constraining digital information processing and conversion to the parts of the spectrum with information of interest.

There are instances, though, where the full 2.5 GHz bandwidth has useful information. Imagine in a cellular base station that should process multiple cell-phones at the same time. In that case, it could make sense with an ADC at the antenna.

What make sense depends on the application.

Filters

A filter can be fully described by the transfer function, usually denoted by $H(s) = \frac{\text{output}}{\text{input}}$.

Most people will today start design with a high-level simulation, in for example Matlab, or Python. Once they know roughly the transfer function, they will implement the actual analog circuit.

For us, as analog designers, the question becomes “given an $H(s)$, how do we make an analog circuit?”” It can be shown that a combination of 1’st and 2’nd order stages can synthesize any order filter. To break down $H(s)$ into first and second order stages we could use symbolic tools like Maple, and maybe it’s even possible in Python these days.

Once we have the first and second order stages, we can start looking into circuits.

First order filter

In the book they use signal flow graphs to show how the first order stage can be generated. By selecting the coefficients $k_0$ ,$k_1$ and $\omega_0$ we can get any first order filter, and thus match the $H(s)$ we want.

I would encourage you to try and derive from the signal flow graph the $H(s)$ and prove to your self the equation is correct.

Try to calculate the transfer function from the figure

Signal flow graphs are useful, we can just follow the instructions.

The instructions are

- any line with a coefficient is a multiplier

- any box output is a multiplication of the coefficient and the input

- any sum, well, sum all inputs

- be aware of gremlins (a sudden -, typing k_1 instead of k_0, etc)

Let’s call the $1/s$ box input $u$

\[u = (k_0 + k_1s)V_i - \omega_0 V_o\] \[V_o = u/s\] \[u = V_o s = (k_0 + k_1s)V_i - \omega_0 V_o\] \[(s + \omega_0)V_o = (k_0 + k_1s)V_i\] \[\frac{V_o}{V_i} = \frac{k_1s + k_0}{s + \omega_0}\]Second order filter

Bi-quadratic is a general purpose second order filter.

Bi-quadratic just means “there are two quadratic equations”. Once we match the $k$’s $\omega_0$ and $Q$ to our wanted $H(s)$ we can proceed with the circuit implementation.

Try to calculate the transfer function from the figure

Follow exactly the same principles as above. If you fail, and you can’t find the problem with your algebra, then maybe you need to use Maple, Mathcad, or SymPy if you must find a transfer function in your future job.

I guess you could also spend hours training on examples to get better at the algebra. Personally I find such tasks mind numbingly boring, and of little value, especially since we today can solve the algebra easily with computers.

What’s important is to be able to setup the equation in the first place.

How do we implement the filter sections?

While I’m sure you can invent new types of filters, and there probably are advanced filters, I would say there is roughly three types. Passive filters, that do not have gain. Active-RC filters, with OTAs, and usually trivial to make linear. And Gm-C filters, where we use the transconductance of a transistor and a capacitor to set the coefficients. Gm-C are usually more power efficient than Active-RC, but they are also more difficult to make linear.

In many AFEs, or indeed Sigma-Delta modulator loop filters, it’s common to find a first Active-RC stage, and then Gm-C for later stages.

Gm-C

In the figure below you can see a typical Gm-C filter and the equations for the transfer function. One important thing to note is that this is Gm with capital G, not the $g_m$ that we use for small signal analysis.

In a Gm-C filter the input and output nodes can have significant swing, and thus cannot always be considered small signal.

gm = Gm ?

NO

Differential Gm-C

In a real IC we would almost always use differential circuit, as shown below. The transfer function is luckily the same.

Differential circuits are fantastic for multiple reasons, power supply rejection ratio, noise immunity, symmetric non-linearity, but the qualities I like the most is that the outputs can be flipped to implement negative, or positive gain.

Calculate the transfer function

The figure below shows a implementation of a first-order Gm-C filter that matches our signal flow graph.

I would encourage you to try and calculate the transfer function.

Given the transfer function from the signal flow graph, we see that we can select $C_x$, $C_a$ and $G_m$ to get the desired $k$’s and $\omega_0$

\[H(s) = \frac{ k_1 s + k_0 }{s + w_o}\] \[H(s) = \frac{s \frac{C_x}{C_a + C_x} + \frac{G_{m1}}{C_a + C_x}}{s + \frac{G_{m2}}{C_a + C_x}}\]Try and calculate the transfer function

Feel free to use a symbolic math tool. The important thing is to figure out how to setup the equations correctly.

Try and figure out how we could make a transconductor

Although you can start with the Gm-C cells in the book, I would acutally choose to look at a few papers first.

The main reason is that any book is many years old. Ideas turn into papers, papers turn into books, and by the time you read the book, then there might be more optimal circuits for the technology you work in.

If I were to do a design in 22 nm FDSOI I would first see if someone has already done that, and take a look at the strategy they used. If I can’t find any in 22 nm FDSOI, then I’d find a technology close to the same supply voltage.

Start with IEEEXplore

I could not find a 22 nm FDSOI Gm-C based circuit on the initial search. If I was to actually make a Gm-C circuit for industry I would probably spend a bit more time to see if any have done it, maybe expanding to other journals or conferences.

I know of Pieter Harpe, and his work is usually superb, so I would take a closer look at A 77.3-dB SNDR 62.5-kHz Bandwidth Continuous-Time Noise-Shaping SAR ADC With Duty-Cycled Gm-C Integrator

And from Figure 10 a) we can see it’s a similar Gm-C cell as chapter 12.5.4 in CJM.

Active-RC

The Active-RC filter should be well know at this point. However, what might be new is that the open loop gain $A_0$ and unity gain $\omega_{ta}$

General purpose first order filter

Below is a general purpose first order filter and the transfer function. I’ve used the condutance $G = \frac{1}{R}$ instead of the resistance. The reason is that it sometimes makes the equations easier to work out.

If you’re stuck on calculating a transfer function, then try and switch to conductance, and see if it resolves.

I often get my mind mixed up when calculating transfer functions. I don’t know if it’s only me, but if it’s you also, then don’t worry, it’s not that often you have to work out transfer functions.

Once in a while, however, you will have a problem where you must calculate the transfer function. Sometimes it’s because you’ll need to understand where the poles/zeros are in a circuit, or you’re trying to come up with a clever idea, or I decide to give this exact problem on the exam.

Try and calculate the transfer function

Let’s work through the calculation.

Step 1: Simplify

The conductance from $V_{in}$ to virtual ground can be written as

$G_{in} = G_1 + sC_1$

The feedback conductance, between $V_{out}$ and virtual ground I write as

$G_{fb} = G_2 + sC_2$

Step 2: Remember how an OTA works

An ideal OTA will force its inputs to be the same. As a result, the potential at OTA$-$ input must be 0.

The input current must then be

$I_{in} = G_{in} V_{in}$

Here it’s important to remember that there is no way for the input current to enter the OTA. The OTA is high impedance. The input current must escape through the output conductance $G_{fb}$.

What actually happens is that the OTA will change the output voltage $V_{out}$ until the feedback current , $I_{fb}$, exactly matches $I_{in}$. That’s the only way to maintain the virtual ground at 0 V. If the currents do not match, the voltage at virtual ground cannot continue to be 0 V, the voltage must change.

Step 3: Rant a bit

The previous paragraph should trigger your spidy sense. Words like “exactly matches” don’t exist in the real world. As such, how closely the currents match must affect the transfer function. The open loop gain $A_0$ of the OTA matters. How fast the OTA can react to a change in voltage on the virtual ground, approximated by the unity-gain frequency $\omega_{ta}$ (the frequency where the gain of the OTA equals 1, or 0 dB), matters. The input impedance of the OTA, whether the gate leakage of the input differential pair due to quantum tunneling, or the capacitance of the input differential pair, matters. How much current the OTA can deliver (set by slew rate), matters.

Active-RC filter design is “How do I design my OTA so it’s good enough for the filter”. That’s also why, for integrated circuits, you will not have a library of OTAs that you just plug in, and they work.

I would be very suspicious of working anywhere that had an OTA library I was supposed to use for integrated filter design. I’m not saying it’s impossible that some company actually has an OTA library, but I think it’s a bad strategy. First of all, if an OTA is generic enough to be used “everywhere”, then the OTA is likely using too much power, consumes too much area, and is too complex. And the company runs the risk that the designer have not really checked that the OTA works porperly in the filter because “Someone else designed the OTA, I just used in my design”.

But, for now, to make our lifes simpler, we assume the OTA is ideal. That makes the equations pretty, and we know what we should get if the OTA actually was ideal.

Step 4: Do the algebra

The current flowing from $V_{out}$ to virtual ground is

\[I_{out}= G_{fb}V_{out}\]The sum of currents into the virtual ground must be zero

\[I_{in} + I_{out} = 0\]Insert, and do the algebra

\[G_{in}V_{in} + G_{out}V_{out} = 0\] \[\Rightarrow - G_{in} V_{in} = G_{out} V_{out}\] \[\frac{V_{out}}{V_{in}} = - \frac{G_{in}}{G_{out}}\] \[= - \frac{ G_1 + s C_1 }{G_2 + sC_2}\] \[= \frac{ -s \frac{C_1}{C_2} - \frac{G_1}{C_2} }{s + \frac{G_2}{C_2}}\]General purpose biquad

A general bi-quadratic active-RC filter is shown below. These kind of general purpose filter sections are quite useful.

Imagine you wanted to make a filter, any filter. You’d decompose into first and second order sections, and then you’d try and match

the transfer functions to the general equations.

The OTA is not ideal

where \(A_0\) is the gain of the amplifier, and \(\omega_{ta}\) is the unity-gain frequency.

In what region does this equation match an ideal integrator 1/sRC response?

At frequencies above $\frac{1}{A_0RC}$ and below $w_{ta}$ the circuit above is a good approximation of an ideal integrator.

See page 511 in CJM (chapter 5.8.1)

Example circuit

One place whwere both active-RC and Gm-C filters find a home are continuous time sigma-delta modulators. More on SD later, for now, just know that SD us a combination of high-gain, filtering, simple ADCs and simple DACs to make high resolution analog-to-digital converters.

One such an example is

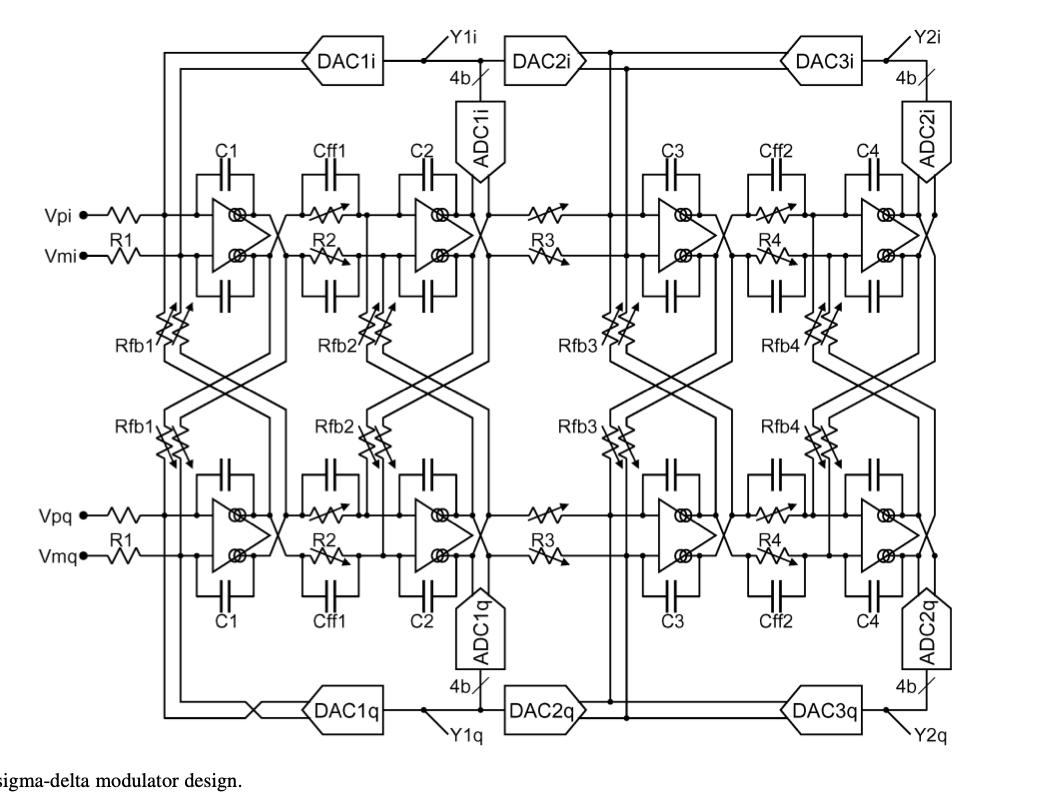

Below we see the actual circuit. It may look complex, and it is.

Not just “complex” as in complicated circuit, it’s also “complex” as in “complex numbers”.

We can see there are two paths “i” and “q”, for “in-phase” and “quadrature-phase”. The fantasitc thing about complex ADCs is that we can have a-symmetric frequency response around 0 Hz.

It will be tricky understanding circuits like this in the beginning, but know that it is possible, and it does get easier to understand.

With a complex ADC like this, the first thing to understand is the rough structure.

There are two paths, each path contains 2 ADCs connected in series (Multi-stage Noise-Shaping or MASH). Understanding everything at once does not make sence.

Start with “Vpi” and “Vmi”, make it into a single path (set Rfb1 and Rfb2 to infinite), ignore what happens after R3 and DAC2i.

Now we have a continuous time sigma delta with two stages. First stage is a integrator (R1 and C1), and second stage is a filter (Cff1, R2 and C2). The amplified and filtered signal is sampled by the ADC1i and fed back to the input DAC1i.

It’s possible to show that if the gain from $V(Vpi,Vpm)$ to ADC1i input is large, then $Y1i = V(Vpi,Vpm)$ at low frequencies.